Centenarians:

The Bonus Years

by Lynn Peters Adler, J.D.

Excerpts Archive

From Chapter 9

The Challenge of Surviving in Today's

Complex Society |

|

...At 102, well-known environmentalist Marjory Stoneman Douglas

of Coconut Grove, Florida, was still at the work that had been

the focus of her life for the past sixty-five years, crusading

for the preservation of the Florida Everglades. In her centennial

year, she traveled to Washington, D.C., to present the annual

National Parks and Conservation Association award to its 1990

recipient. Named in her honor, the award recognizes others for

their outstanding efforts in environmental protection of the

country's national parks. |

Marjory Stoneman Douglas at her home, sharing

her views on advanced age. Photograph by Susan Greenwood, 1990 |

|

Author of The Everglades: River of Grass, a seminal ecological

work, Mrs. Douglas was instrumental in creating the Everglades

National Park in 1947. In 1969, she formed the volunteer activist

group Friends of the Everglades. She continues to be active in

the National Everglades Coalition, in efforts to protect several

endangered species, to conserve the coral reefs of Key Largo,

and to preserve the historic homes of Coconut Grove. At age ninety-eight,

she completed her autobiography, Voice of the River, and

began writing a biography of the English naturalist writer William

Henry Hudson.

"At 100, I have a sense of achievement and a sense of

leisure as well," she said. "I'm not pushed as much

as I was. Old age can be more relaxing and more contemplative.

I'm enjoying it more than middle age."

For people of advanced age, the heart of the matter of belonging

in today's society is that they ought to be able to choose their

lifestyle in later years, just as they were free to do when younger,

and not be deterred or discouraged from doing so because of their

age. If elderly people want to be involved in some aspect of

community life or simply to be present at community events and

social activities, they should be made to feel welcome and invited

to participate to the extent they desire and that is possible

for them. This is a moral imperative to be acted upon by society

and individuals alike, on behalf of these deserving citizens

who have contributed and been a part of so much of the greatness

of America. |

|

From Chapter 7

Challenges to Physical Health |

|

When he was eighty-five, Oscar Wilmeth

decided he wanted to live to be 100. He had already survived

a near-fatal accident in his eightieth year. He was driving on

a high mountain road in the Colorado Rockies, on the last leg

of a 10,000 mile solo motor trip around the country, when, he

recalled, "I blacked out and went off the road and down

into a ravine!" It was hours before help arrived. "The

doctors gave me up for dead and called in my family from California.

But I fooled 'em." |

Oscar Wilmeth achieves his goal of living to be 100.

Photograph by Laurette Alexander. |

|

After undergoing multiple surgeries to mend his broken bones,

he spent several months doing intensive physical therapy because

he had to learn to walk again. Once out of the hospital, he bought

another car, promising his worried son he'd be careful. "The

altitude got me, that's all," he insisted.

At ninety, Oscar suffered a heart attack. Once again, he was

not expected to survive, but he did. He was given a pacemaker.

He learned about exercising and eating right. In fact, after

his heart attack, he changed his diet completely, giving up sugar,

chocolate, and fried foods — which he had always loved —

in favor of a low-fat diet.

For a while, Oscar lived on his own. He kept active and exercised

regularly. Then at the age of ninety-seven, he had a stroke,

which left him partially paralyzed on his right side. Physical

therapy enabled him to regain much of his former functioning,

but he had to make some adjustments, such as giving up driving.

Finding it hard to write by hand, he taught himself to type on

a portable electric typewriter, which he used to keep up with

his correspondence of dozens of letters a month to family and

friends. He also began typing his autobiography — in anticipation

of his 100th birthday: "Looking back over the years of my

life, I would say that maintaining one's health is the most important

thing to do with one's life. All too often we put it aside to

earn a living or to care for others. I've been lucky. But not

everyone can depend on luck or good genes to get them through

to a "ripe, old age!" I think it's wonderful to see

younger people taking such an interest in health and exercise

and diet. I'm all for it— for people of all ages. It's never

too late to take good care of yourself!"

Oscar began planning his centennial celebration when he turned

ninety-eight. He booked the ballroom at the local Hilton and

invited more than 200 people. At ninety-nine, however, he came

down with pneumonia and began to worry if he would reach his

goal. So he moved into a small group home, where he had a room

of his own and his meals were provided. A nurse's aide was in

attendance day and night. Oscar bought an oxygen tank and mask

to keep handy in his room when he had difficulty breathing; he

also bought two new hearing aids and a hand-held device that

increased the volume on the television so he could watch his

favorite programs. His eyesight failing, Oscar went from bifocals

to trifocals. As he said: "I did everything I could to take

care of myself and tried to get information on the latest developments

in vitamins, and all those newfangled devices to help with functioning,

short of a wheelchair — I draw the line there.

All in all, it's a pretty good time to be old. There are so

many medical miracles nowadays that help keep people alive, such

as my pacemaker, and so many new ways of diagnosing disease and

then being able to cure it early on before it really takes hold.

We're never as young as we used to be, but we can stay in pretty

good shape for the shape we're in when we're old, if we work

at it and take advantage of all the miracles out there. And they

are miracles to me because I remember when I was young growing

up on a farm and my grandfather came to live with us. He was

old and there was nothing anyone could do for him except make

him comfortable. He died of old age, the doctor said. Today we

don't have to settle for that. We can get a diagnosis and try

to fix the ailment a lot of times. But you have to ask for it

sometimes. You just can't be complacent. I remember when I was

still in my seven-ties, I complained to my doctor that I had

a pain in my leg; he said it was just old age. I told him that

my other leg was just as old and asked how come it didn't hurt.

I found another doctor who treated me for the arthritis in my

leg. That's what you have to do-you have to make sure you get

the medical attention and not just let anyone pass it off to

'old age' and give up on you."

On his 100th birthday, Oscar was triumphant. He greeted each

of his 200 guests and spoke to them on and off for four hours,

giving the highlights of his life. When he cut his birthday cake,

he jokingly introduced a woman sixty years his junior, a personal

friend whom he called upon to share in this ceremony, as his

girlfriend. "That shook things up a bit," he said,

chuckling. |

From Chapter 4:

The American Experience |

|

Centenarian Ola Canion had it right when she remarked during

an oral history taping, "Why, heck, I don't remember exactly

— it was around 1905!" Ola was being questioned about

what year an historical event occurred. And then she went on

to chide the interviewer, "That was eighty-five years ago.

I'll bet you can't remember the exact dates of some things that

happened twenty-five years ago. Besides, it's not important —

you can go look that up. What I'm telling you is the background

of what went on at that time, and that I do remember. And that's

what you can't find in a history book!" |

Ola Canion at 100, in her mother's dress,

shawl and bonnet from 1905. Photo courtesy of the Dorothy Garske

Center, Phoenix, AZ. Photograph by Don B. Stevenson. |

|

Ola adds flavor to her account of the family's migration from

one state to another by telling how she and her family traveled

from Texas to southern Arizona in a covered wagon in the early

years of this century. "We children, and the women, had

to walk most of the way," she says, "to make room for

our possessions and to save on the horses. But whenever we went

through a town, my father told us to get in the wagon so the

townsfolk wouldn't think badly of him for making us walk. I was

mad at this, though, because I had my mind set that I was walking

all the way from Texas to Arizona. Since I was the oldest, I

refused to get in with the others, and so today I can say that

I walked all the way. No, I don't recall the year exactly-it

was around 1905," she quips.

On special occasions, Ola wears her mother's dress and bonnet

worn on that journey.

What centenarians and others of advanced age have to say makes

history dynamic by preserving personal insights of events, people,

and places. Their recollections make the past come alive, as

alive as the person speaking. In the process, it creates a more

memorable piece of history. Centenarians are able to push recollections

of history back at least another generation by relating stories

they heard, firsthand, from their parents, uncles, and aunts.

Sometimes their recollections go back even further to their grandparents'

experiences in the mid-nineteenth century, from stories they

enjoyed as youngsters and remember still. |

Challenges to The Mind

I wish medical science would come up with a way

for people

to age with their minds intact.

— Helen Cope, 101 Greenwich, Connecticut

The most fundamental

and frightening loss that can be encountered as one ages, elders

tell us, is losing the ability to think, remember, and reason.

As Mary Gleason, at 101, puts it, "I can live with the loss

of my sight, and if my hearing goes, well, so be it—as long

as I can keep my marbles—that’s the most important

thing."

Mildred Reiger would concur. She and her twin

sister, Adeline Moran, turned 100 on April 11, 1993. "My

eyesight is troublesome," Millie says. "I can hardly

see anything on TV anymore. I can take care of myself and I still

go to the Senior Citizens Friendship Club and go out as often

as I can. But my sister just sits in a chair now; she has slipped

a lot since our birthday. We have someone who lives with us to

take care of her."

Millie finds it strange that she and her twin

should be so different now. With relish, she repeats the family

story of their birth: "No one knew our mother was expecting

twins, so we were a real surprise. The doctor delivered me and

carried me out to the kitchen to hand me over to my aunt. Going

back to tend to my mother, at the doorway he exclaimed, ‘There’s

another one!’ My sister was already lying on the bed. We

are five minutes apart. We have always enjoyed being twins."

Millie continues, "We have had a wonderful life. For the

past thirty years, we have lived together in Addie’s home

in Evanston, Illinois. It’s so sad to see Addie like this

now. I don’t think she even recognizes me anymore."

It is indeed puzzling how some people can

remain alert and mentally functional for 100 years, and more,

while others, even a twin or other sibling, may not. It is generally

accepted that some mental slowing and changes do occur as a person

ages. Lately, however, it is evident through scientific research

and observations of older people themselves that total mental

incapacity is not the inevitable companion of old age. Rather,

severe mental incapacity is a consequence or result of disease

or some other medical problem.

In his book Aging Well, Dr. James Fries

of Stanford University Medical School notes that most of the

time the slowing down in reaction and response times associated

with aging is benign and of little practical importance unless

one becomes unduly preoccupied with the changes and "dwells

on it." That is unnecessary, he contends, and only makes

things worse. Our brains are incredibly sophisticated and powerful,

and it is foolish to think of them |

as though they were simply some form of long-life

battery that follows a uniform path of decline. In the absence

of disease, the capacity to learn new things and new skills and

the ability to be creative is always there. So, too, are inspirational

exam-ples of centenarians (and others of advanced age) who are

proving this to be true.

Demonstrating that one is never too old to learn, Centenarian

Selma Plaut made the news when she received a bachelor of arts

degree from the University of Toronto. Mrs. Plaut, who fled Nazi

Germany, even-tually settled in St. Paul, Minnesota. In her seventies,

she moved to Toronto to be near her son. At age eighty-eight,

she began auditing classes of interest to her in theology, Jewish

history, and French. She did so well that she decided to take

further classes for credit and to work toward a degree. Although

she was short a few credits, the university awarded her the degree

in commemoration of her centennial; she graduated in June with

the class of 1990—100 years from her birth. |

Selma Plaut, age 100, and Sadie Lewis may

be separated by 78 years, but they joined together in receiving

degrees at the University of Toronto.

Photograph by M. Slaughter, used with permission from the Toronto Star. |

|

On Physical Mobility

… We are physically fit when we have the heart and lung

(aerobic) capacity to pump oxygen to the muscles, sufficient

muscle strength to accomplish reasonable tasks, and flexibility

in the joints to permit movement. When it comes to maintaining

physical mobility, the simple axiom "use it or lose it"

says it all.

… In New York City, former professional dancer Milton Feher

has also developed a combination of exercise, relaxation, and

dance that he has been teaching for almost fifty years. Milton

was forced to retire from the Broadway stage in 1941 due to arthritis

in his knees. "It happened all of a sudden," he tells.

Milton’s very successful career, performing in such popular

shows as Song of Norway and I’d Rather be Right

by George M. Cohan, was cut short in its prime by the affliction

that limits so many older people. "I then developed a way

to cure myself after I gave up on doctors," he explains,

"and I’ve been teaching people of all ages ever since.

The concept is to relax into a straight line and to keep the

body centered. The problem people have, and the reason so many

older people fall, is that people are moving their weight off

their feet. The key is to always feel that your body is resting

on your feet and not let it get away from you. It sounds simple,

but it takes concentration and practice."

Milton’s star pupil, Claire Willi, 100, credits his work

with her over the last thirty years to getting her to the century

mark. "There are two things that older people fear most,"

she confides, "falling apart and falling down. Exercising

regularly, learning how to use one’s body correctly, in

balance, and using relaxation techniques improve flexibility

and coordination and help with both. Exercise keeps you younger,

no matter what your chronological age," Claire says with

certainty, and from experience.

At age seventy, Claire, who emigrated from Switzerland almost

fifty years earlier, felt old. She never exercised, tired easily,

and never walked for pleasure because her feet hurt when she

did. She was starting to stoop and shuffle her feet when she

moved and used a small pillow under her dress to hide her swayed

back. A beautiful woman, Claire minded the changes that age was

bringing. She had led an exciting life, happily married to one

of the largest champagne dealers in New York and was a celebrated

hostess. Her career, she says, was helping her husband by entertaining

and running their personal life, managing their schedules and

their three homes in Florida, Pennsylvania, and New York. It

bothered her tremendously that at seventy she felt like an old

woman and beyond hope.

Quite coincidentally, while in a health food restaurant in her

neighborhood near Carnegie Hall, she overheard a waitress tell

another customer about the marvelous dance lessons she was taking,

which not only invigorated her and improved her posture but also

relaxed her. "My ears perked up at this," Claire recalls.

She made her way to the Milton Feher School of Dance and Relaxation

on West Fifty-eighth Street, located in an apartment building

she could see from her building. There, above the din of city

traffic, she began attending classes three times a week plus

some individual lessons. Claire has been a regular student ever

since. She attributes Milton’s training to what now keeps

her healthy, beautiful, and graceful at age 100. She wears a

leotard and leggings and her body is trim and shapely. Claire

and Milton, an octogenarian, have been featured in numerous magazines

over this last decade as a true success story, including Prevention

Magazine (January, 1992) in an article entitled "Dance

Away Arthritis Pain!"

"Claire has succeeded in staving off the loss of mobility

that so often accompanies advanced age. She keeps up with people

half her age in the one-hour dance class, and afterward, as has

been her practice for these thirty years, she takes a long walk

in Central Park," Milton tells. Claire advises, "It’s

never too late to begin." |

|

HOW OLD WOULD YOU BE IF YOU DIDN’T

KNOW HOW OLD YOU WAS?—Satchel Page

There seems to be a current consensus among lay people and

experts alike that, given reasonably good health, feeling old

is largely a state of mind, making the quote from Satchel Page,

the ageless baseball hero, prophetic. Ever so many people at

100 and over say they don’t feel old in their minds and

in their spirits. Mature, yes—in the sense of years lived

and wisdom acquired and experience garnered—but not old

in the sense of being worn out and used up.

Such a large number of centenarians say they do not consider

themselves old that there must be something here for us to appreciate.

Certainly, everyone’s physical appearance and ability changes

with the years; this fact of life, no doubt, contributes to the

negative individual and societal conventions surrounding old

age. Often not taken into account, though, because it is not

readily apparent or discussed, and usually not revealed unless

one gets to know people who have lived a long time, is the encouraging

and equally important fact that a person’s inner self —

one’s spirit — does not necessarily grow old, or age

in keeping with one’s chronological years or appearance.

"Perhaps people should be given an individual choice of

when they would like to be considered old or a senior citizen,"

offers Billy Earley. She continues to declare, "I don’t

feel old and I don’t think of myself as old (in a negative

sense) at 105." Billy’s viewpoint is a frequent refrain

heard from active centenarians who insist that a person’s

inner self does not have to keep up chronologically with one’s

physical years. As one centenarian confided, "Over the years,

I would be surprised when I would unexpectedly catch a glimpse

of myself in a store window while passing or in a mirror to see

that I looked older; but inside I felt about the same.

I did not feel my chronological age, and I still don’t.

I feel young inside. There are times when I think to myself that

I don’t feel my age, and then I wonder, ‘Well, what

age do I feel?’ I’ve determined it’s around thirty.

I don’t think I’ve ever felt like fifty." Adds

Billy, "To my mind, I’m sometimes thirty, fifty, or

sixty. On bad days, I may feel like seventy, but whatever, I

do not feel 100 years plus." |

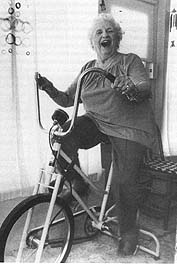

Billy Earley at home on her

exercise bicycle.

Photograph by Tina Romano. Photo courtesy of Billy Earley. |

Centenarians tell their stories:

Centenarians talk about what life was like before the invention

of the radio, television and motion pictures; for home entertainment,

they relied on reading, social gatherings with neighbors and

friends, storytelling and reading out loud to each other, singing,

playing piano and playing games. They speak of the excitement

of the times, as innovations in communication and entertainment

became a part of their daily lives — their own "Age

of Enlightenment," as Louis Kelly (103, of Scottsdale, Arizona)

dubbed it. "The beginning of the radio in the late 1800s

began the revolution in communications," he says with certainty.

"The first radios I recall were called crystal sets. They

were introduced about 1901 and you could build them yourself

if you were handy. The vacuum tube, which made radios able to

be mass produced, had not yet been invented. Early ‘crystal’

receivers, as they were called, operated without electricity

or batteries, and the signals they picked up were very weak.

If someone had one, however, all the neighbors would gather around

at night. The operator, usually the owner and builder, used a

crystal detector, which was a metal wire coming into contact

with a metal sulfide crystal, to pick up the signal — that

is, try to pick up the signal. They were very fickle. Sometimes

you could spend the whole evening searching for one and give

up, disappointed." Still, many centenarians remember the

thrill of hearing a voice from miles and miles away coming through

the headphones when the signal was picked up.

The early radio programs were mostly music: dance orchestras,

such as the Cliquot Club Eskimos playing popular music of the

time, lively and with a catchy beat, centenarians recall. The

first electric radios came out after World War I. A popular program

was the dance orchestra, the A and P Gypsies in 1923. By the

end of the 1920s, pro-grams were more sophisticated and included

drama hours, such as the "Eveready Hour" and "Great

Moments in History". In 1928, there was the "Music

Appreciation Hour" over the Blue Network with Walter Damrosch,

which was very popular, centenarians say. The only other was

called the Red Network.

"When we were young, the moon was an image for romance and

love songs and nursery rhymes," Louis muses. "Imagine

seeing men walking on that moon, brought to us through the miracle

of technology. It’s amazing — ‘awesome’ as

my college student great-grandson would say. I think it’s

the most incredible thing I’ve witnessed in all these 100

years. And brought right into our living rooms through television."

- top - |